1. Release notes

-

Add some assembly and C code regarding fork, execve, inline assembly and .section .bss

-

Add a link to the very nice and fancy Searchable Linux Syscall Table for x86 and x86_64

-

Add GDB (The GNU Debugger) explanation

-

Move some regarding killing the program and exiting the GDB

-

Add info regarding GDB his display, info and auto-display features

-

-

Add write to file example using system calls for Create, Open, Write and Close file

-

Add explaination regarding printing local variables

-

In main.c a small demo regarding invoking the write C-library function

-

Add printing using local variables on the stack

-

Improve toc

-

Better examples, scripts

-

Restructure all the files in separate (project name) dirs

-

Add GDB related options

-

Implement some assignments from the book: Programming from the ground up

-

More files from the book Programming from the ground Up

-

Initial release

2. Todos

Create some C code which prints the args e.g. int main(int argc, char* argv) { … }

You might review the Process Creating Assembly and C below in 2021! :-) for now it rocks!

-

Nieuwe sources (.s files) uitleggen

-

plaatjes inserten uit src/main/asciidoc/images

-

documents inserten uit src/main/asciidoc/files

3. Introduction

Below you find some Assembly I made.

The Assembly is sorted per topic and grows harder and heavier the farther you go …

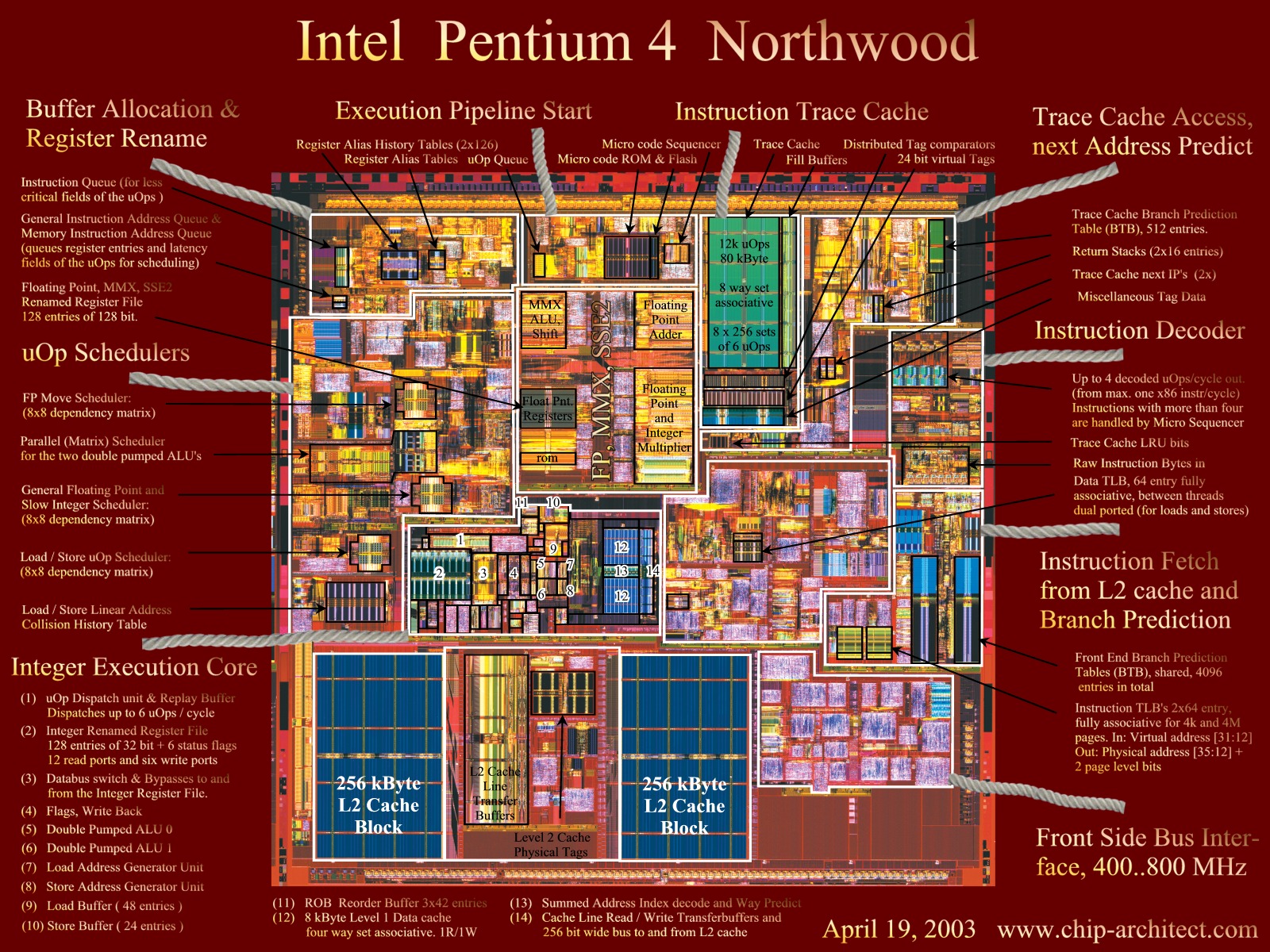

4. Architecture & Images

rloman hier boven de uitleg over dit plaatje plaatjes uit files/Register.txt

5. Scripts used during this document

Scripts used in this document. They will be used to run the assembly code

#!/bin/bash

as --gstabs+ ./$1.s -o $1.o

ld ./$1.o

./a.out

echo $?#!/bin/bash

as --32 --gstabs+ $1.s -o $1.o

ld -m elf_i386 $1.o

./a.out

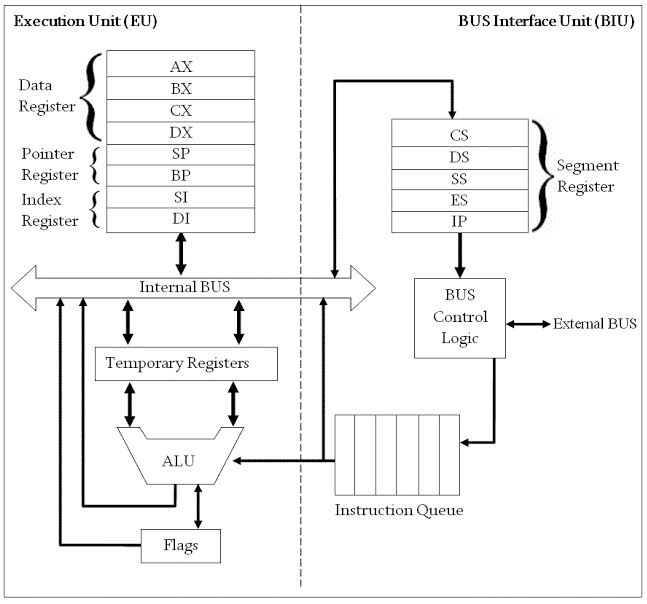

echo $?6. Registers

Although the main registers (with the exception of the instruction pointer) are "general-purpose" in the 32-bit and 64-bit versions of the instruction set and can be used for anything, it was originally envisioned that they be used for the following purposes

-

AL/AH/AX/EAX/RAX: Accumulator

-

BL/BH/BX/EBX/RBX: Base index (for use with arrays)

-

CL/CH/CX/ECX/RCX: Counter (for use with loops and strings)

-

DL/DH/DX/EDX/RDX: Extend the precision of the accumulator (e.g. combine 32-bit EAX and EDX for 64-bit integer operations in 32-bit code) (so called Data Register?)

-

SI/ESI/RSI: Source index for string operations.

-

DI/EDI/RDI: Destination index for string operations.

-

SP/ESP/RSP: Stack pointer for top address of the stack.

-

BP/EBP/RBP: Stack base pointer for holding the address of the current stack frame.

-

IP/EIP/RIP: Instruction pointer. Holds the program counter, the address of next instruction.

-

CS: Code

-

DS: Data

-

SS: Stack

-

ES: Extra data

-

FS: Extra data #2

-

GS: Extra data #3

x86 processors have a collection of registers available to be used as stores for binary data. Collectively the data and address registers are called the general registers. Each register has a special purpose in addition to what they can all do

-

AX (accumulator) multiply/divide, string load & store

-

BX index register for MOVE

-

CX count for string operations & shifts

-

DX port address for IN and OUT

-

SP points to top of the stack

-

BP points to base of the stack frame

-

SI points to a source in stream operations

-

DI points to a destination in stream operations

-

IP instruction pointer

-

FLAGS

-

segment registers (CS, DS, ES, FS, GS, SS) which determine where a 64k segment starts (no FS & GS in 80286 & earlier)

-

extra extension registers (MMX, 3DNow!, SSE, etc.) (Pentium & later only).

The IP register points to the memory offset of the next instruction in the code segment (it points to the first byte of the instruction). The IP register cannot be accessed by the programmer directly.

mov ax, 1234h ; copies the value 1234hex (4660d) into register AX

mov bx, ax ; copies the value of the AX register into the BX registermov $1234, %rax # copies the value 1234hex (4660d) into register AX

mov %rax, %rbx # copies the value of the AX register into the BX register7. Addressing

This is how you write indexed addressing mode instructions in assembly language

-

movl BEGINNINGADDRESS(,%INDEXREGISTER,WORDSIZE)

mov data_items(,%edi,4), %eax # in this case the data_items is pointer to an address8. BSS section

The .bss section is a static memory section that contains buffers for data to be declared at runtime.

This buffer memory is zero-filled.

In the .bss section, you can’t set an initial value.

This is useful for buffers because we don’t need to initialize them anyway, we just need to reserve storage.

.section .bss

.lcomm my_buffer, 500This directive, .lcomm, will create a symbol, my_buffer , that refers to a 500-byte storage location that we can use as a buffer.

.section .bss

.lcomm my_buffer, 500 # .lcomm::= local common area (private), where .comm::= common area

.section .data

file: .string "./hello.keep" # File to read from

.section .text

.globl _start

_start:

open_a_file:

mov $2, %rax # sys_open

mov $file, %rdi # file

mov $0644, %rsi # Read/Write permissions

syscall

read_file_into_buffer:

mov %rax, %rdi # fd should be in %rdi (64 bits)

mov $my_buffer, %rsi

mov $500, %rdx

mov $0, %rax

syscall

print_buffer:

mov %rax, %rdx # message string length (readed before entered the number of bytes in %rax)

## sys_write(stream, message, length)

mov $1, %rax # sys_write is syscallnr. 1

mov $1, %rdi # the fd for stdout is 1

mov $my_buffer, %rsi # message address

syscall

close_the_file:

mov $3, %rax # syscallnr. 3 is close, and rdi still contains the fd

syscall

exit:

mov %rdx, %rdi #the status code for the exit systemcall should be in %rdi, in this case the bytes read

mov $60, %rax # now the rax register contains 60 which is the systemcall number for the exit syscall

syscall #invoke the system call9. Assembly for starters

9.1. Exit (64 bits)

9.1.1. What: Exit

This topic will show how to perform an exit system call using an syscall instruction

| The program will produce strange results if any number is greater than 255, because that’s the largest allowed exit status using the exit system call |

9.1.2. How: Exit

-

set 60 to the %rax

-

set the return status code to the %rdi registger, e.g. 3

-

invoke a software interrupt using the 64bit x86 syscall instruction

9.1.3. Source: Exit

.section .text

.globl _start

_start:

mov $60, %rax # 60 is the syscall number for 64-bits assembly

mov $3, %rdi # the status code for the exit systemcall should be in %rdi

syscall #invoke the system call#!/bin/bash

as --gstabs+ ./$1.s -o $1.o

ld ./$1.o

./a.out

echo $?./64bit.sh exit

39.2. Exit (32 bits)

9.2.1. What: Exit

This topic will show how to perform an exit system call using an int instruction

9.2.2. How: Exit

-

set 1 to the %eax

-

set the return status code to the %ebx, e.g. 5

-

invoke a software interrupt using the int instruction

9.2.3. Source: Exit

.section .text

.globl _start

_start:

movl $1, %eax # now the eax register contains 1 which is the systemcall number for the exit syscall

movl $5, %ebx #the status code for the exit systemcall should be in %ebx

int $0x80 #invoke the system call#!/bin/bash

as --32 --gstabs+ $1.s -o $1.o

ld -m elf_i386 $1.o

./a.out

echo $?./32bit.sh exit

59.3. Hello world (64 bit)

9.3.1. What: Hello world!

This topic shows the classic example: printing Hello world in Assembly

|

It uses the write(…) systemcall

Syntax ⇒ write(int fd, char* message, int length)

|

-

1 ⇒ write to stdout

-

message ⇒ the message to write

-

13 ⇒ the length of the message

9.3.2. How: Hello world

-

set $1 to the accumulator %rax: the syscallnr. (1) and use the following parameters ⇒

-

set $1 to the %rdi: the fd, stdout

-

set the address of the to be printed string in the %rsi register

-

set the length in the %rdx register

-

9.3.3. Source: Hello world

.section .text

.global _start

_start:

# write(1, message, 13)

mov $1, %rax # system call 1 is write

mov $1, %rdi # file handle 1 is stdout

mov $message, %rsi # address of string to output

mov $13, %rdx # number of bytes

syscall # invoke operating system to do the write

# exit(0)

mov $60, %rax # system call 60 is exit

xor %rdi, %rdi # we want return code 0

syscall # invoke operating system to exit

message:

.asciz "Hello, world\n"#!/bin/bash

as --gstabs+ ./$1.s -o $1.o

ld ./$1.o

./a.out

echo $?./64bit.sh hello

=> Hello, world

=> 09.4. Printing a numeric value

9.4.1. What: Printing a numeric value

This topic shows how to print a numeric value to the console

The print-int-32.s example shows how to print using native assembly instructions

The printvalue.s example shows how to print using the C-library printf function

9.4.2. How: Printing a numeric value

-

set $4 to the accumulator %eax: the syscallnr. (4) and use the following parameters ⇒

-

set $1 to the %ebx: the fd, stdout

-

set the address of the to be printed string in the %ecx register

-

set the length in the %edx register

-

invoke the kernel using the int $0x80 instruction

-

Create a format string

-

set the first parameter ⇒ the address of the format string in register %rdi

-

set the second parameter ⇒ the to be printed integer in %rsi (in this case 312)

-

cleanup the accumulator (%rax)

-

invoke the printf using the call printf assembly instruction

9.4.3. Source: Printing a numeric value

Source: print-int-32.s

.section .text

.globl _start

_start:

movl $4, %eax # sys_write function code

movl $1, %ebx # file descriptor (sysout)

movl $string, %ecx # starting address of string

movl $length, %edx # length of string

int $0x80 # transfer to kernel with code 0x80 (system call) to print the above

movl $1, %eax # sys_exit function code

movl $0, %ebx # return code 0 (OK)

int $0x80 # transfer to kernel and exit program

string:

.asciz "33\n"

strend:

length = strend - string#!/bin/bash

as --32 --gstabs+ $1.s -o $1.o

ld -m elf_i386 $1.o

./a.out

echo $?./32-bit.sh print_int_32

=> 33Source: printvalue.s

.section .data

.section .text

.global _start

_start:

format:

.asciz "%d\n"

mov $format, %rdi # set 1st parameter (format)

mov $312, %rsi # set 2nd parameter (current_number)

xor %rax, %rax # because printf is varargs

# Stack is already aligned because we pushed three 8 byte registers

call printf # printf(format, current_number)

exit:

mov $60, %rax # system call 60 is exit

xor %rdi, %rdi # we want return code 0

syscall # invoke operating system to exit#!/bin/bash

#-e main -s eventueel toevoegen als het startsymbol anders heet dan _start (rloman dit nog weg of uitzoeken)

as --gstabs+ -o $1.o ./$1.s

ld -dynamic-linker /lib64/ld-linux-x86-64.so.2 -lc -melf_x86_64 ./$1.o

./a.out./do_with_link.sh printvalue

=> 3129.5. Printing local variables

9.5.1. What: Printing local variables

-

using a pop version

-

using a move from %rsp

Especially show attention to the used .format string with is used during the printf C-library function call

And when you are interested in why the %rax register is zero’d during te invoke of the printf function then follow this link

The rest of the code below should be self explaining.

9.5.2. Source: Printing local variables

.section .data

.section .text

.global _start

_start:

push $77

format:

.asciz "%d\n" # this format may also be below or above in .section .data but needed

# 1 (pop - version)

mov $format, %rdi # set 1st parameter (format)

pop %rsi # set 2nd parameter (current_number)

xor %rax, %rax # mov $0, %rax using xor (faster) and because printf is varargs

call printf # printf(format, current_number)

# 2 (move the content of %rsp to %rsi - version)

mov $format, %rdi # set 1st parameter (format)

mov (%rsp), %rsi # set 2nd parameter (current_number)

xor %rax, %rax # because printf is varargs

call printf # printf(format, current_number)

exit:

mov $60, %rax # system call 60 is exit

xor %rdi, %rdi # we want return code 0

syscall # invoke operating system to exit#!/bin/bash

#-e main -s eventueel toevoegen als het startsymbol anders heet dan _start (rloman dit nog weg of uitzoeken)

as --gstabs+ -o $1.o ./$1.s

ld -dynamic-linker /lib64/ld-linux-x86-64.so.2 -lc -melf_x86_64 ./$1.o

./a.out./do_with_link.sh print_local_stack_var

=> 779.6. Write to file

9.6.1. What: Write to file

-

Create

-

Open

-

Write

-

Close

9.6.2. Source: Write to file

.section .data

message: .asciz "Hello World!\n" # message and newline

strend: length = strend - message # this is the length of the string (dynamic)

file: .string "./hello.out" # File to write

.section .text

.global _start

_start:

open_file:

## sys_open(file, permissions)

mov $2, %rax # sys_open

mov $file, %rdi # file

mov $0644, %rsi # Read/Write permissions

syscall

check_if_exists:

## File exists?

mov $0, %rdx

cmp %rax, %rdx

jle write

create:

## sys_create(file, permissions)

mov $85, %rax # sys_create

mov $file, %rdi # file

mov $0644, %rsi # Read/Write permissions

syscall

test_creation:

## File created sucessfully?

mov $0, %rdx

cmp %rdx, %rax # the %rax now contains the file descriptor and test for value <= 0

jle exit

write:

mov %rax, %rbx # File descriptor copy

## sys_write(stream, message, length)

mov $1, %rax # sys_write is syscallnr. 1

mov %rbx, %rdi # the fd

mov $message, %rsi # message address

mov $length, %rdx # message string length

syscall

# close the file

# rdi still contains the fd

mov $3, %rax # syscallnr. 3 is close

syscall

exit:

## sys_exit(return_code)

mov $60, %rax # sys_exit

mov $0, %rdi # return 0 (success)

syscall#!/bin/bash

as --gstabs+ ./$1.s -o $1.o

ld ./$1.o

./a.out

echo $?./64bit.sh write_to_file

=> 0

$ cat ./hello.out

=> Hello World!10. Advanced Assembly

10.1. The Set Directive

10.1.1. What: The Set Directive

This topic will demo how to use Assembler Directives

10.1.2. How: The Set Directive

The code is pretty heavy but rather self explaining. Since if you reached this part of the document, the part above should be obvious and you can read on here …

10.1.3. Source: The Set Directive

.global _start

.section .text

.set sys_write, 1

.set stdout, 1

.set sys_exit, 60

_start:

mov $sys_write, %rax # system call 1 is write

mov $stdout, %rdi # file handle 1 is stdout

mov $message, %rsi # address of string to output

mov $14, %rdx # number of bytes

syscall # invoke operating system to do the write

# exit(0)

mov $sys_exit, %rax # system call 60 is exit

mov $0, %rdi # we want return code 0

syscall # invoke operating system to exit

message:

.asciz "Hello, world\n"#!/bin/bash

as --gstabs+ ./$1.s -o $1.o

ld ./$1.o

./a.out

echo $?./64bit.sh hello_world_using_set_directive_64_bit

=> Hello, world10.2. Add (64 bit)

10.2.1. What: Add (64 bit)

This topic will show how to add using 64 bit assembly instruct.

10.2.2. How: Add (64 bit)

Adding is done by adding some values to the %rax register also called the accumulator

In this example there will be a number in the accumulator the %rax register and in the %rbx They will be added to the %rax The result will be moved to %rdi since that will be result code of the exit systemcall

10.2.3. Source: Add (64 bit)

.section .data:

.section .text

.globl _start

_start:

mov $5, %rax

add $3, %rax

mov %rax, %rdi #the status code should be in %rdi

mov $60, %rax # exit system call number

syscall #invoke the system call#!/bin/bash

as simple_add.s -o simple_add.o

ld simple_add.o

./a.out

echo $?./simple_add.sh

1310.3. Calling a Function

10.3.1. What: Calling a Function

This topic will show how to declare and call a function

10.3.2. How: Calling a Function

| The stack grows downwards |

-

optional: push the parameters on the stack

-

invoke the function using the call assembly instruct

-

the call instruct does nothing more than jump to a label

-

-

save the base pointer ⇒ push %rbp

-

make the stack pointer the base pointer ⇒ mov %rsp, %rbp

-

do something in the function body

-

e.g. move the first parameter, again parameter to %rax ⇒ mov 24(%rbp), %rax

-

e.g. add the second parameter to %rax ⇒ add 16(%rbp), %rax

-

-

restore the stack pointer ⇒ mov %rbp, %rsp

-

restore the old (pushed) base pointer - to be able to recursive calls ⇒ pop %rbp

-

return using the ret instruct

-

the stack now contains the old %rip

-

pop that and go back to that address

-

returning the value of %rax as the result of the function

-

-

Optional: clean up the parameters

-

By adding 8bytes / parameter to the stack pointer e.g. 2 vars: add $16, %rsp

-

10.3.3. Source: Calling a Function

# this file is even created by the src/main/scripts/assapp script

.section .text

.globl _start

_start:

push $5

push $3

call add

# set back the stack to before the call (e.g. remove the pars)

add $16, %rsp

mov %rax, %rdi #the status code for the exit systemcall should be in %rdi, in this case the result of the add function

mov $60, %rax # now the rax register contains 60 which is the systemcall number for the exit syscall

syscall #invoke the system call

add:

# save the base pointer

push %rbp

# make the stack pointer the base pointer

mov %rsp, %rbp

# move the first parameter, again parameter to %rax, be aware that the top of the %rbp, points to the saved base pointer, hence 8+2*8

mov 24(%rbp), %rax

# add the second parameter to %rax, see above for explaination

add 16(%rbp), %rax

# restore the stack pointer

mov %rbp, %rsp

# restore the old (pushed) base pointer, to be able to recursive calls

pop %rbp

ret#!/bin/bash

as --gstabs+ ./$1.s -o $1.o

ld ./$1.o

./a.out

echo $?./64bit.sh function-and-call

=> 810.4. Add using a Function call (32 bit)

10.4.1. What: Add (32 bit)

This topic will show how to add using 32 bit assembly function call

10.4.2. How: Add (32 bit)

Adding is done here using a function call

10.4.3. Source: Add (32 bit)

#PURPOSE:Program to illustrate how functions work. This program will compute 8+5

.section .data

.section .text

.globl _start

_start:

pushl $8 # place 8 on the top of the stack

pushl $5 # place 5 on the top of the stack hence the stack is now: [8,5] (top is right in the example)

call add # invoke the add function

addl $8, %esp # when done, the %esp (stack pointer) is incremented by 8, hence pointing back to before the first pushed value above

movl %eax, %ebx # set the content of the accumulator in the the %ebx register (the resulting statuscode)

movl $1, %eax # (and %ebx is the status code (the result))

int $0x80 # And exit

# This function adds to numbers

# variables:

## %eax - holds the first number (a)

## %ebx - holds the second number (b)

## -4(%ebp) - holds the current result

## %eax - used for temporary storage

.type add, @function

add:

pushl %ebp # save old base pointer

movl %esp, %ebp # make stack pointer the base pointer

#subl $8, %esp # get room for our local storage # not perse neede here

movl 8(%ebp), %eax # put second (pushed) argument in %ecx which is the FIRST parameter!!! (a)

movl 12(%ebp), %ebx # put first (pushed) argument in %ebx which is the SECOND parameter!!! (b)

addl %ebx, %eax

# kind a local var this

movl %eax, -4(%ebp) # store current result not perse neede here

# this is a small one, but for later calculation using the local var (1) is handy

movl -4(%ebp), %eax # return value goes in %eax # not perse needed here since already in accumulator.

movl %ebp, %esp # restore the stack pointer

popl %ebp # restore the base pointer

ret # return from function#!/bin/bash

as --32 --gstabs+ add.s -o add.o

ld -m elf_i386 add.o

./a.out

echo $?./add.sh

1310.5. Add plus One incl. local variable

10.5.1. What: Add plus One

This topic will show how to perform result = a+b+1

10.5.2. How: Add plus One

Adding is done here using a function call and there will be one added

10.5.3. Source: Add plus One

.section .text

.set sys_write, 1

.set stdout, 1

.set sys_exit, 60

.global _start

_start:

#push the first argument on the stack

push $21

# push the second argument on the stack

push $34

# call the function

call add_plus_one

# add 8 bytesx2 (one 64 bit var) to remove the arguments from the stackframe

add $16, %rsp

# perform exit(%rdi);

mov %rax, %rdi

mov $sys_exit, %rax

syscall

.type add_plus_one, @function

add_plus_one:

# save %rbp and move %rsp to %rbp

## this is to save the %rbp for recursive calling

push %rbp

mov %rsp, %rbp

# create room for a (one) local variable

#move the stack pointer 8 (x8)=64 bits down for one 64bit local variable

## and that will be used below to store our intermediate

sub $8, %rsp

# add the first(24(%rsbp)) and second(16(%rbp)) parameterto the %rax register

mov 24(%rbp), %rax

add 16(%rbp), %rax

# increment with one

inc %rax

# set the content of the %rax to the local variable, just for demo purposes

mov %rax, -8(%rbp)

# set the (final) result in the accumulator (%rax), since that will be returned using the ret instruction below

mov -8(%rbp), %rax

#restore the stack pointer

mov %rbp, %rsp

# restore the (saved) basepointer

pop %rbp

# and return from function, which returns the content of the %rax register, after popping to the %rip, so it returns to the

# next instructions after the caller

ret#!/bin/bash

as --gstabs+ ./$1.s -o $1.o

ld ./$1.o

./a.out

echo $?./64bit.sh add_plus_one

5610.6. Remainder operator (%)

10.6.1. What: Remainder operator

This topic will demo how to calculate the remainder of two arguments

10.6.2. How: Remainder operator

Suppose we want to calculate the remainder of a/b e.g. a = 8003 and b = 100

8003 ⇒ %eax 100 ⇒ %ecx

When we execute the div instruct, then

%ecx contains the result (80) %edx contains the remainder, 3 in our example

10.6.3. Source: Remainder operator

.section .text

.globl _start

_start:

xor %ecx, %ecx # clear dividend

movl $8003, %eax # argument 1

movl $100, %ecx # argument 2

div %ecx # arg1/arg2 => %ecx

movl %edx, %ebx # move the remainder (in %edx) to %ebx (for status code)

exit:

movl $1, %eax # exit

int $0x80 # invoke the system call#!/bin/bash

as --32 --gstabs+ $1.s -o $1.o

ld -m elf_i386 $1.o

./a.out

echo $?./32bit.sh remainder

=> 310.7. Max of three

10.7.1. What: Max of three

This topic will demo how to find the max of three variables

10.7.2. How: Max of three

This example shows the compare and the jump instruct, the rest seems pretty self explaining - after having seen the code above

10.7.3. Source: Max of three

.section .data

var1: .int 40

var2: .int 20

var3: .int 30

.section .text

.globl _start

_start:

# move the contents of variables

movl (var1), %ecx

cmpl (var2), %ecx

jg check_third_var

movl (var2), %ecx

check_third_var:

cmpl (var3), %ecx

jg _exit

movl (var3), %ecx

_exit:

movl $1, %eax

movl %ecx, %ebx

int $0x80#!/bin/bash

as --32 --gstabs+ $1.s -o $1.o

ld -m elf_i386 $1.o

./a.out

echo $?./32bit.sh max_of_three_global_vars

=> 4011. Complex Assembly

11.1. Max of a set of numbers

11.1.1. What: Max of a set of numbers

This topic will demo how to find the max of a set of numbers

11.1.2. How: Max of a set of numbers

This example shows the compare and the jump instruct, the rest seems pretty self explaining - after having seen the code above

11.1.3. Source: Max of a set of numbers

#PURPOSE:This program finds the maximum number of a set of data items.

# Credits Book Programming from the Ground up (see Resources)

#VARIABLES: The registers have the following uses:

# %edi - Holds the index of the data item being examined

# %ebx - Largest data item found

# %eax - Current data item

## WARNING: Since the statuscode of a C program < 255, the max number in the list

## below should be 255

# The following memory locations are used:

# data_items - contains the item data. A 0 is used to terminate the data

.section .data

#These are the data items

data_items:

.long 3,67,34,222,45,75,54,34,44,33,22,11,66,0

.section .text

.globl _start

_start:

movl $0, %edi # move 0 into the index register

movl data_items(,%edi,4), %eax # load the first byte of data from data_items[%edi] into %eax upto and not including the 4(th) byte (long!)

movl %eax, %ebx # since this is the first item, %eax is the biggest

start_loop:

cmpl $0, %eax # check to see if we’ve hit the end

je loop_exit # exit the loop if they are equal

incl %edi # else load next value

movl data_items(,%edi,4), %eax

cmpl %ebx, %eax # compare values => jle means below compare the content of %eax with %ebx and if eax < ebx do nothing, jump if eax le ebx so other way

jle start_loop # if less or equal go to start loop (the new one is not bigger, e.g. the new one is le )

movl %eax, %ebx # else, move the value as the largest

jmp start_loop # uncondition jump to start of the loop

loop_exit: # we are done now

movl $1, %eax #1 is the exit() syscall

# %ebx is the status code for the exit system call and it already has the maximum number

int $0x80#!/bin/bash

as --32 --gstabs+ $1.s -o $1.o

ld -m elf_i386 $1.o

./a.out

echo $?./32bit.sh maximum_of_a_set

=> 22211.2. Min of a set of numbers

11.2.1. What: Min of a set of numbers

This topic will demo how to find the minimum of a set of numbers

11.2.2. How: Min of a set of numbers

This example shows the compare and the jump instruct, the rest seems pretty self explaining - after having seen the code above

11.2.3. Source: Max of a set of numbers

#PURPOSE:This program finds the minimum number of a set of data items.

#VARIABLES: The registers have the following uses:

# %edi - Holds the index of the data item being examined

# %ebx - Largest data item found

# %eax - Current data item

# The following memory locations are used:

# data_items - contains the item data. A 0 is used to terminate the data

.section .data

#These are the data items

data_items:

.long 67,34,3,222,45,75,54,34,44,33,22,11,66,255

.section .text

.globl _start

_start:

movl $0, %edi # move 0 into the index register

movl data_items(,%edi,4), %eax # load the first byte of data from data_items[%edi] into %eax upto and not including the 4(th) byte (long!)

movl %eax, %ebx # since this is the first item, %eax is the smallest

start_loop:

cmpl $255, %eax # check to see if we’ve hit the end

je loop_exit # exit the loop if they are equal

incl %edi # else load next value

movl data_items(,%edi,4), %eax

cmpl %ebx, %eax # compare values

jg start_loop # if less or equal go to start loop (the new one is not bigger, e.g. the new one is le )

movl %eax, %ebx # else, move the value as the smallest

jmp start_loop # uncondition jump to start of the loop

loop_exit:

movl $1, %eax # exit with the status code in the %ebx register

int $0x80#!/bin/bash

as --32 --gstabs+ $1.s -o $1.o

ld -m elf_i386 $1.o

./a.out

echo $?./32bit.sh minimum

=> 311.3. Fibonacci

11.3.1. What: Fibonacci

This topic will demo how to print the first 90 fibon numbers and shows how to invoke the C-library printf function

11.3.2. How: Fibonacci

This assembly code has to be explained more rloman … rloman en het script do_with_link is prima maar die -e main mag weg???

11.3.3. Source: Fibonacci

# -----------------------------------------------------------------------------

# A 64-bit Linux application that writes the first 90 Fibonacci numbers. It

# needs to be linked with a C library.

#

# Assemble and Link:

# gcc fib.s

# -----------------------------------------------------------------------------

.global _start

.text

_start:

push %rbx # we have to save this since we use it

mov $90, %rcx # rcx will countdown to 0

xor %rax, %rax # rax will hold the current number, now zero (xor is faster than mov $0, %rax)

xor %rbx, %rbx # rbx will hold the next number, idem, now zero

inc %rbx # rbx is originally 1

.type print, @function

print:

# We need to call printf, but we are using eax, ebx, and ecx. printf

# may destroy eax and ecx so we will save these (by pushing on the stack) before the call and

# restore them afterwards.

push %rax # caller-save register

push %rcx # caller-save register

mov $format, %rdi # set 1st parameter (format)

mov %rax, %rsi # set 2nd parameter (current_number)

xor %rax, %rax # because printf is varargs

# Stack is already aligned because we pushed three 8 byte registers

# printf(format, current_number) (calls the C-library function, not to be confused with a syscall)

call printf

pop %rcx # restore caller-save register

pop %rax # restore caller-save register

mov %rax, %rdx # save the current number

mov %rbx, %rax # next number is now current

add %rdx, %rbx # get the new next number

dec %rcx # count down

jnz print # if not done counting, do some more print (comparing with %rcx)

pop %rbx # restore rbx before returning

#exit

mov $60, %rax

mov $0, %rdi

syscall

format:

.asciz "%20ld\n"#!/bin/bash

#-e main -s eventueel toevoegen als het startsymbol anders heet dan _start (rloman dit nog weg of uitzoeken)

as --gstabs+ -o $1.o ./$1.s

ld -dynamic-linker /lib64/ld-linux-x86-64.so.2 -lc -melf_x86_64 ./$1.o

./a.out./do_with_link.sh fibon

0

1

1

2

3

5

8

13

21

...

177997941600471418911.4. Power operator

11.4.1. What: Power operator

This topic will demo how to calculate the result of a number raised to the power of anumber number

11.4.2. How: Power operator

The code is pretty heavy but rather self explaining. Since if you reached this part of the document, the part above should be obvious and you can read on here …

11.4.3. Source: Power operator

#PURPOSE:Program to illustrate how functions work. This program will compute the value of 2^3 + 5^2

# Credits Book Programming from the Ground up (see Resources)

.section .data

.section .text

.globl _start

_start:

pushl $3 # place 3 on the top of the stack

pushl $2 # place 2 on the top of the stack hence the stack is now: [3,2] (top is right in the example)

call power # invoke the power function

addl $8, %esp # move the stack pointer back (4bytes per argument)

pushl %eax # push the (sub) result (the content of the accumulator) on the stack

###### now the second power invocation

pushl $2 # push second argument

pushl $5 # push first argument

call power # again, call power

addl $8, %esp # move the stack pointer back

popl %ebx # since we saved it before 'push %eax' (line 15) we can now pop that old result in %ebx register

#eax now contains the result of the 2^5 call

addl %eax, %ebx # add them to the %ebx register

movl $1, %eax # (and %ebx is the status code (the result))

int $0x80 # And exit

# This function raises number to a power

# variables:

## %ebx - holds the base number

## %ecx - holds the power to raise to

## -4(%ebp) - holds the current result

## %eax - used for temporary storage

.type power, @function

power:

pushl %ebp # save old base pointer

movl %esp, %ebp # make stack pointer the base pointer

subl $4, %esp # get room for our local storage

movl 8(%ebp), %ebx # put first argument in %ebx

movl 12(%ebp), %ecx # put second argument in %ecx

movl %ebx, -4(%ebp) # store current result to local var 1

power_loop_start:

cmpl $1, %ecx # if the power is 1, we are done

je end_power

movl -4(%ebp), %eax # move the current result into %eax

imull %ebx, %eax # multiply the current result by the base number

movl %eax, -4(%ebp) # store the current result

decl %ecx # decrease the power

jmp power_loop_start # run for the next power

end_power:

movl -4(%ebp), %eax # return value goes in %eax

movl %ebp, %esp # restore the stack pointer

pop (%ebp) # restore the base pointer

ret # return from function#!/bin/bash

as --32 --gstabs+ $1.s -o $1.o

ld -m elf_i386 $1.o

./a.out

echo $?./32bit.sh power

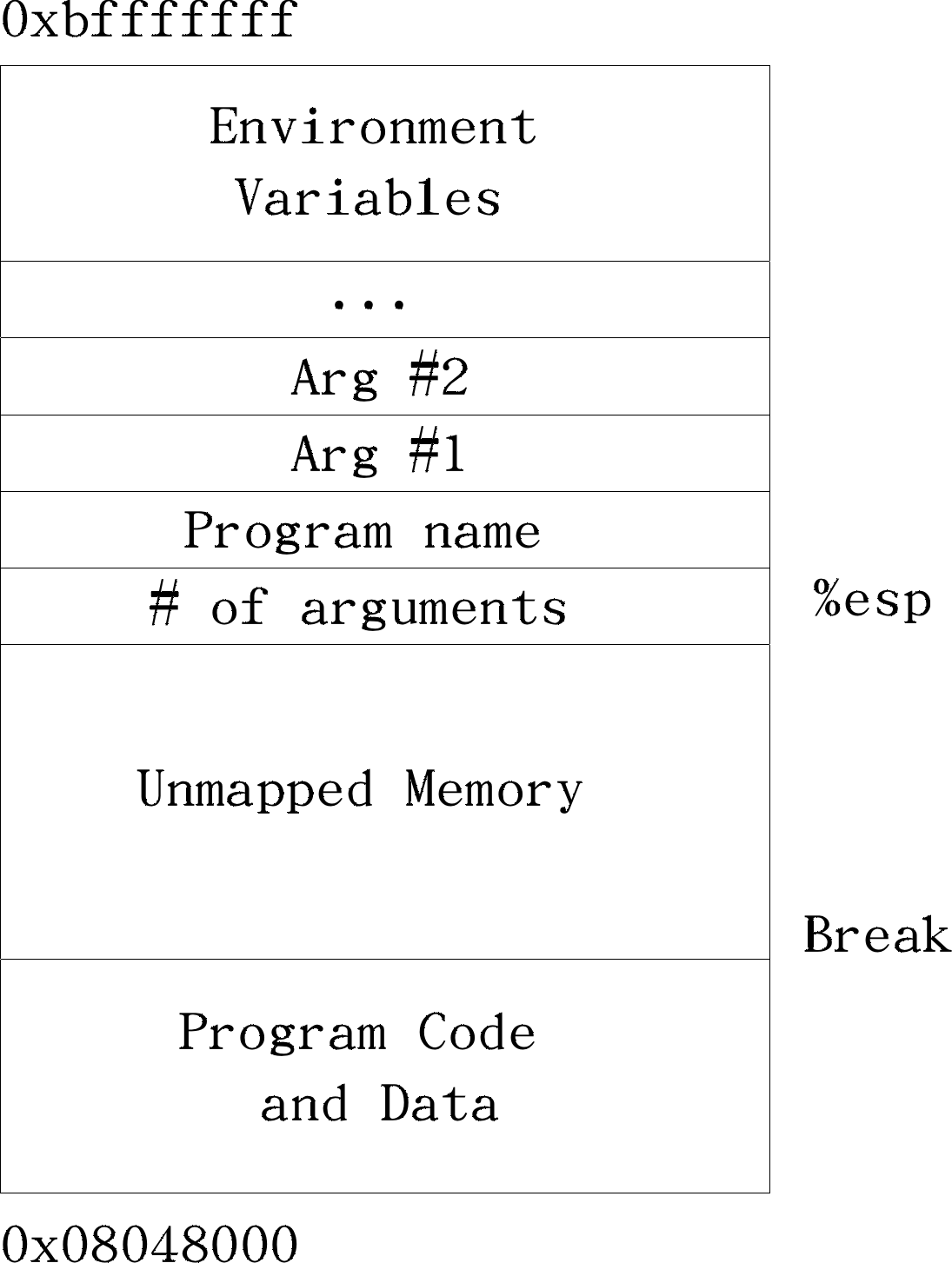

=> 33 # since 2^3 +5^2 = 3311.5. Printing arguments

11.5.1. What: Printing arguments

This topic will demo how to iteratore over and print arguments supplied in the commandline

11.5.2. How: Printing arguments

The code is pretty heavy but rather self explaining. Since if you reached this part of the document, the part above should be obvious and you can read on here …

11.5.3. Source: Printing arguments

SYS_WRITE = 1

STDOUT = 1

.section .data

newline: .ascii "\n"

newline_end: NEWLINE_LEN = newline_end-newline

.section .text

.globl _start

_start:

mov (%rsp), %r8 # 0(%rsp) = # args. This code doesn't use it. Only save it to R8 as an example.

lea 16(%rsp), %rbx # 8(%rsp)=pointer to prog name, # 16(%rsp)=pointer to 1st parameter

.argloop:

mov (%rbx), %rsi # Get current cmd line parameter pointer

test %rsi, %rsi

jz .exit # If it's zero we are finished

# Compute length of current cmd line parameter

# Starting at the address in RSI (current parameter) search until

# we find a NUL(0) terminating character.

# rdx = length not including terminating NUL character

xor %rdx, %rdx # RDX = character index = 0

mov %rdx, %rax # RAX = terminating character NUL(0) to look for

.strlenloop:

inc %rdx # advance to next character index

cmpb %al, -1(%rsi,%rdx)# Is character at previous char index

# a NUL(0) character?

jne .strlenloop # If it isn't a NUL(0) char then loop again

dec %rdx # We don't want strlen to include NUL(0)

# Display the cmd line argument

# sys_write requires:

# rdi = output device number

# rsi = pointer to string (command line argument)

# rdx = length

#

mov $STDOUT, %rdi

mov $SYS_WRITE, %rax

syscall

# display a new line

mov $NEWLINE_LEN, %rdx

lea newline(%rip), %rsi # We use RIP addressing for the

# string address

mov $SYS_WRITE, %rax

syscall

add $8, %rbx # Go to next cmd line argument pointer

# In 64-bit pointers are 8 bytes

# lea 8(%rbx), %rbx # This LEA instruction can replace the

# ADD since we don't care about the flags

# rbx = 8 + rbx (flags unaltered)

jmp .argloop

.exit:

xor %rdi, %rdi

mov $60, %rax

syscall#!/bin/bash

as --gstabs+ ./$1.s -o $1.o

ld ./$1.o

./a.out

echo $?./a.out aap noot mies

=> aap

=> noot

=> mies11.5.4. Resources: Printing arguments

I used this link regarding Cycle Through and Print argv array in x64 ASM - Stack Overflow which was pretty helpful

12. Process Creation

12.1. Assembly instructions

.section .text

.global _start

_start:

# fork using 57 syscallnr.

mov $57, %rax

syscall

# write(1, message, 13)

mov $1, %rax # system call 1 is write

mov $1, %rdi # file handle 1 is stdout

mov $message, %rsi # address of string to output

mov $13, %rdx # number of bytes

syscall # invoke operating system to do the write

# exit(0)

mov $60, %rax # system call 60 is exit

xor %rdi, %rdi # we want return code 0

syscall # invoke operating system to exit

message:

.asciz "Hello, world\n".section .data

pid: .asciz " The pid is: %d\n"

ppid: .asciz "The ppid is: %d\n"

.section .text

.globl _start

_start:

mov $39, %rax # getpid system call

syscall

mov $pid, %rdi # set 1st parameter (format)

mov %rax, %rsi # set 2nd parameter (current_number)

xor %rax, %rax # because printf is varargs

call printf # printf(format, current_number)

mov $110, %rax # getppid system call (get parent pid!)

syscall

mov $ppid, %rdi # set 1st parameter (format)

mov %rax, %rsi # set 2nd parameter (current_number)

xor %rax, %rax # because printf is varargs

call printf # printf(format, current_number)

mov $0, %rdi #the status code for the exit systemcall should be in %rdi

mov $60, %rax # now the rax register contains 60 which is the systemcall number for the exit syscall

syscall #invoke the system call.section .data

ls:

.asciz "/bin/ls"

.section .text

.global _start

_start:

mov $ls, %rdi # %rdi must contain the address of the filename (in this case the address of the ls var above)

lea 8(%rsp), %rsi # %rsi must contain the address of argv, lea::= Load Effective Address

## in this case, skip over the command itself and start with 8 bytes above the command to find the argv

mov $0, %rdx # %rdx contains the environment, zero, null, nada for now

mov $59, %rax # system call 59 is execve

syscall # invoke operating system to do the write

# no need to exit, since execve replaces stack, heap, data and text section12.2. C instructions

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <unistd.h>

#include <sys/types.h>

int main() {

// make two processes which run same program after this instruction

fork();

printf("Hello world!\n");

return 0;

}#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <unistd.h>

#include <sys/types.h>

int main() {

if(fork()) { // parent

printf("Hello world parent!\n");

}

else { // child

printf("Hello world child!\n");

}

return 0;

}#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <unistd.h>

#include <sys/types.h>

int main() {

// make two processes which run same program after this instruction

pid_t pid = fork();

if(pid) { // parent

printf("Hello world parent! (child pid is:%d)\n", pid);

}

else { // child

printf("Hello world child! (child pid is:%d)\n", pid);

}

return 0;

}// pid_t waitpid( pid_t pid, int * stat_loc, int options );

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <unistd.h>

#include <sys/types.h>

#include <sys/wait.h>

int main() {

// make two processes which run same program after this instruction

int childExitStatus;

int pid = fork();

if(pid) { // parent

// wait

int result = waitpid(pid, &childExitStatus, 0);

printf("Hello world parent! (child pid is:%d)\n", pid);

int actual_exit = WEXITSTATUS(childExitStatus);

printf("Exit status of child: %d\n", actual_exit);

}

else { // child

printf("Hello world child! (child pid is:%d (should be zero here))\n", pid);

}

return 7;

}#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <unistd.h>

#include <sys/types.h>

int main() {

pid_t r;

if(fork()) { // parent

printf("Hello world parent!\n");

}

else { // child

printf("Hello world child!\n");

char* args[] = {"ls", "-l", "-t", "-r", NULL};

r = execv("/bin/ls", args);

// :-) this statement below will NOT be executed. You know why?

printf("execv result => %d\n", r);

}

return r;

}13. Inline Assembly in C

| This only works with 32 bit assembly |

-

%0 is output var (line 0 is the first)

-

%1 is input var (line 1 is the second)

-

The last line is the 'clobbered' list registers, which do not need an extra '%' prefix

-

You reach for a register in inline assembly with an extra prefixed '%' e.g. %eax ⇒ %%eax

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <unistd.h>

#include <sys/types.h>

int main() {

int in=10;

int out;

asm("mov %1, %%eax;" // instead of SEMICOLON could also finish this line with \n\t

"mov %%eax, %0;"

:"=r"(out) /* output */

:"r"(in) /* input */

:"%eax" /* clobbered register(s) */

);

printf("Result: %d\n\n", out);

// nog 1

asm("mov %1, %%eax\n"

"add %%eax, %0"

:"=r" (out)

:"r" (in)

:"%eax"

);

printf("Output is: %d\n", out);

int result = 0;

int x = 103;

int y = 102;

asm ("mov %1, %0;"

"add %2, %0;"

: "=r" (result)

: "r" (x), "r" (y)

:"%eax"

);

printf("The result of adding using two input-parameters is: %d\n", result);

return 0;

}14. GDB

During this section we will learn you how to debug an x86 assembly app

| The commands in the debugger below can almost all be abbrevated |

(gdb) info breakpoints

(gdb) i b # same effect14.1. Enabling the debugging

-

Add --gstabs or --gstabs+ to add debugging information

$ as --gstabs+ ./hello_world.s -o hello_world.o

$ ld hello_world.o14.2. Running the debugging

$ gdb a.out$ (gdb) help(gdb) l(gdb) run [arg1][args] ...(gdb) show args(gdb) run aap noot mies

Starting program: /home/rloman/repo/assembly-onderzoek/src/main/assembly/hello-world/a.out aap noot mies

Breakpoint 1, _start () at ./hello.s:7

7 mov $1, %rax # system call 1 is write

(gdb) show args

Argument list to give program being debugged when it is started is "aap noot mies".

(gdb)14.3. Registers

(gdb) info register

(gdb) info registers(gdb) info register rax14.4. Using breakpoints

(gdb) break <lineNumber> (gdb) break label (gdb) break *addr # set a breakpoint at memory address (gdb) break fn # set a breakpoint at the beginning of function 'fn'

(gdb) nexti

(gdb) n(gdb) stepi

(gdb) s(gdb) finish(gdb) info breakpoints(gdb) continue(gdb) clear(gdb) disable(gdb) enable(gdb) delete [bpnum1] [bpnum2] ## deletes the breakpoints or all if none specified14.5. Examining the call stack

(gdb) where(gdb) backtrace(gdb) frame(gdb) up

(gdb) down14.6. Examining Registers and Memory

-

x(hexadecimal)

-

u (unsigned decimal)

-

o (octal)

-

a(address)

-

c (character)

-

f (floating point)

Print the content of a register reg using format f

(gdb) print/u $rdi # print the content of register %rdi using format unsigned intPrint the contents of memory address addr using repeat count r, size s, and format f . Repeat count defaults to 1 if not specified. Size can be b (byte), h(halfword), w (word), or g (double word). Size defaults to word if not specified. Format is the same as for print, with the additions of s (string) and i (instruction).

(gdb) x/1wu _start # display the contents of address **_start** once, in word and expecting an unsigned intAt each break, print the contents of register reg using format f

(gdb) display/u $rdi # example to print the content of register %rdi every break in (expecting) unsigned int formatAt each break, print the contents of memory address addr using size s (same options as for the x command)

(gdb) display/w _start # print the content of the address at label start per breakpointShows a numbered list of expressions set up to display automatically at each break.

(gdb) info display

Auto-display expressions now in effect:

Num Enb Expression

2: y /u $rdiRemove displaynum from the display list

(gdb) undisplay 1 # removes the number 1 entry which is found during info display14.7. Killing the program

(gdb) kill14.8. Exiting GDB

(gdb) quit-

See Page 289 of the book Programming from the ground up

15. General resources

-

$ gcc -c hello.s && ld hello.o && ./a.out

-

%rax is always required to be loaded with the system call number

-

The standard name of the start label is _start, zie exit.s

-

Handy command: $ stat <file> shows some stat(istics) regarding a file

-

Kernel note: A thread is a proces with a shared address space

16. Further reading

A fundamental introduction to x86 assembly programming |

https://www.nayuki.io/page/a-fundamental-introduction-to-x86-assembly-programming |

Using AS |

|

A good to read Wikibooks regarding X86 Assembly |

|

x64 Cheat Sheet |

|

Searchable Linux Syscall Table for x86 and x86_64 |

|

The GNU Assembler explained |

|

AS explained |

|

Intel code table (old) |

|

Versions of Hello World in C and Assembly |

https://montcs.bloomu.edu/~bobmon/Code/Asm.and.C/hello-asms.html |

Printing integers in NASM Assembly |

https://stackoverflow.com/questions/6903435/nasm-linux-assembly-printing-integers |

Linux 2.xx Syscalls intro (German) |

|

x86 Architecture |